Author: Jung Woo Kim

Artist: Jordan Mooney

Editor: Katie Kavanagh

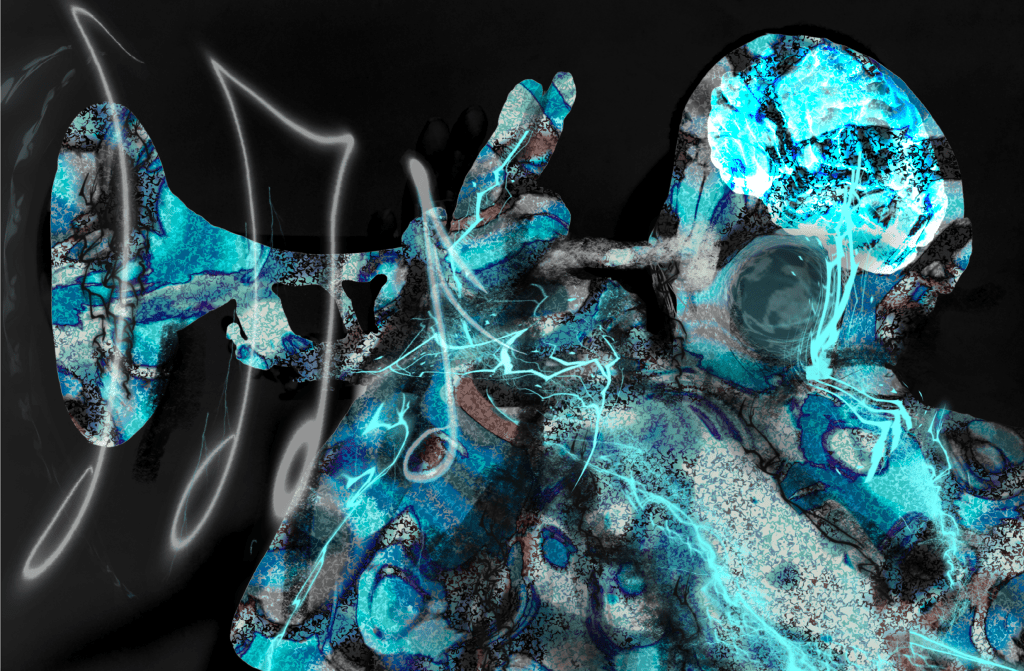

Your tenor saxophone glistens gold in the dim lights of the jazz bar. You and your band are playing the last few notes of the main melody, and you begin to take your solo. You play a melody which soars over the familiar chord changes, weaving in and out of the key like a needle through cloth. You finish with a trill on a high E flat, and the crowd applauds as the trumpet player picks up right where you left off, beginning their own solo. The question is: what on earth was going through your head?

Jazz musicians differ from classically-trained musicians in that they take solos, an improvisational section where players compose a melody on the fly. The best players draw from their own practice and the repertoire of great jazz musicians before them, all the while listening to the rest of the band and responding in real time. In other words, jazz solos require both a high level of technical ability and creativity. Though this has a steep learning curve, over time musicians gain confidence and learn to get ‘into the zone’ during a solo, feeling a simultaneous sense of effortlessness and intense focus. Sometimes, they forget that time is passing, and the rest of the world slips from view, leaving only them, their instrument, and their accompanying band. This feeling has a name, coined by psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi, called ‘flow.’

Think back to a time when you were completely absorbed in some activity, just difficult enough to keep you hyper-focused and lost in the intrinsic thrill of the activity. That is the flow state, and it can arise from sports to video games, from painting to, of course, playing music. Put simply, it is a state of mind where your attention is held by some engaging, enjoyable task. Csíkszentmihályi states that there are six components to achieving the flow state: intense focus on the present, synthesis of action and consciousness, loss of self-consciousness, a sense of control, a distorted perception of time, and an intrinsic motivation to experience the activity. He also claims that achieving the flow state results in a greater sense of satisfaction for the individual experiencing it.

This link between the flow state and jazz improvisation was studied by Vergara et al. in 2021 by using functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) techniques on the brain. Jazz improvisation was of particular interest to these researchers as a model to study spontaneous creativity. This is because jazz musicians do not get to revise their solos once they’ve played them, compared to outputs that are not made in real-time, like writing or painting. It was theorised that creativity involved an interplay between the free generation of ideas and the self-evaluation of ideas. Notably, the former is governed by a brain network called the Default Mode Network (DMN), and the latter by the Executive Control Network (ECN). You can think of the first as the daydreamer, while the second is the director who decides which of their thoughts will be translated into action. By taking fMRI readings of 12 professional jazz pianists, they found the areas of the brain that are most active during improvisation.

The researchers recorded the brain activity of the pianists when playing pre-learned music. This allows them to determine what areas are functioning as the pianists play. Then, they recorded their brain activity when improvising a novel melody over some chord changes on the piano, with their voice, and in their imagination. By subtracting the pre-learned piano brain activity from the improvised piano brain activity, they found that activity in the DMN (self-expression and idea generation) was increased, while activity in the ECN (idea monitoring and evaluation) was decreased. This was replicated in the imagined and vocalised improvisation experiments. In other words, jazz improvisation is linked to decreased inhibition and increased mind-wandering, regulated by the interactions between multiple brain networks which may also reflect a state of flow.

What does this mean for jazz musicians? Firstly, accessing the flow state may be key to pulling off a good solo. This means practising in order to improve your technical ability until playing becomes automatic. On top of that, you’ll need to take creative risks and play without excessive self-censoring. Ultimately, if you ever find yourself taking a jazz solo: just go with the flow.