Climate change might be far less gender-neutral than we thought

Author: Azita Vatandost

Artist: Rahel Kiss

Editor: Altay Shaw

The climate crisis, as universally felt as it is, unfortunately shows gestures of bias by targeting certain groups in society. As much as the climate crisis, through our general perspective, is the melting of the ice caps and the rising of the sea levels, it is also equally the enforcement of gender inequality. The interface between climate change and gender inequality is predominantly visible in low and middle-income countries as a result of cultural norms that support bigotry of men. Therefore, there is unequal opportunity in the accessibility of education, healthcare and employment.

The majority of the agricultural sector in developing countries is women, such as within the regions of Eastern Africa and South Asia. In particular, ⅔ of small-scale farming in South Asia is constituted by women. Women’s heavy presence in agriculture and being subsistence farmers can be explained by how 75% of women are a part of the informal economy because of unequal employment rights. Consequently, to support their wellbeing and their family, they become increasingly more dependent on acquiring natural resources. In the instances of drought and fluctuating rainfall, there will be pressure for women to work more in order to obtain these necessary resources. Due to unpredictable weather conditions, food sources are threatened which in turn threatens the livelihoods of women.

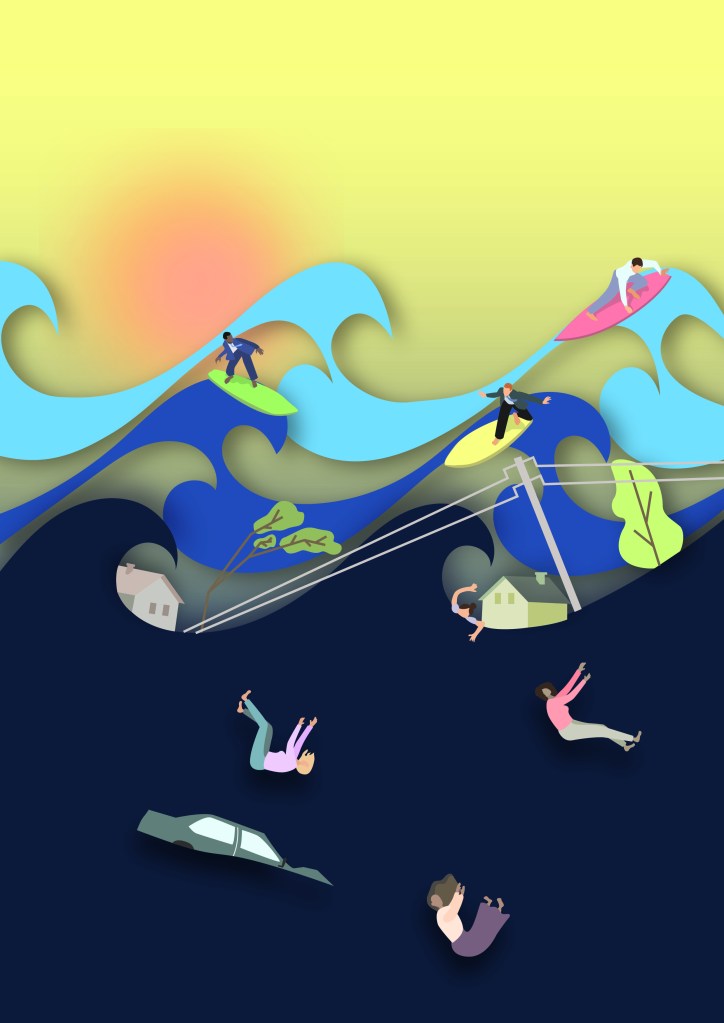

We see natural disasters as genderless—they do not take place for the purpose of discrimination or at least, they shouldn’t. However, the aftermath is regrettably sexist. Women are less likely to survive and seek out assistance after natural disasters because of pre-existing inequalities in social mobility that prevent their accessibility to disaster planning and evacuation response. To illustrate, the aftermath of the Indian Ocean tsunami in 2004 showed that 70% of deaths were women. With an increase in natural disasters by five-fold over 50 years, the disparity in deaths between men and women continues to amplify gender inequality.

Within extreme climate hazards, women’s health is further threatened. Extreme heat can significantly increase the occurrence of still birth and the transmission of vector-borne illnesses. Meanwhile, displacement due to natural disasters limits pregnant women’s right to receive sufficient aid to support pre and post-natal care. Ultimately, 68% of women were recorded to suffer adverse health effects out of 130 studies conducted.

But then again, climate change shouldn’t cherry pick who needs to suffer more or less, it should not have to cause suffering: but, why does it?

It all boils down to policymakers in government. The gender balance or lack thereof in government is essentially a direct reflection of gender inequality enforced by the climate crisis. If we are unable to have a balance of gender in our respective governments across the globe, how are we meant to eliminate the adverse aftermath that climate change continues to cause? Across the world, 21% of women are government policymakers. In the EU alone, only 26.8% of policymakers for environment and sustainability are women. Thus, information on climate adaptation strategies are inevitably catered towards men, which can be seen in agriculture. This is prevalent in Uganda and Senegal where men have more awareness in the implementation of climate-smart agriculture. Therefore, having gender balance in government would potentially ensure that needs for all genders could be adequately met.

There is a dire need for policymakers to adopt more gender-responsive climate adaptation strategies to combat gender inequality. Could policies that focus on implementing briefings towards marginalized women affected by climate change become the next step?

A good post on climate crisis and gender inequality. Thank you 🌍🙏

LikeLike