Writer: Ayden Wee

Editor: Altay Shaw

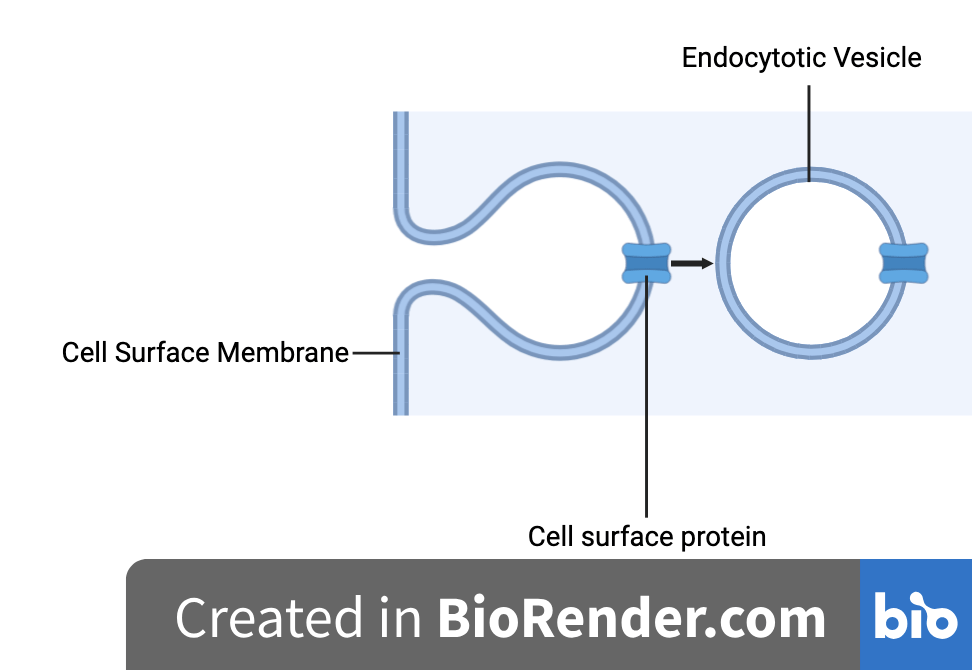

Here’s a diagram most students of A-level biology have seen before:

Figure 1: A diagram depicting early endocytosis. (Created using Biorender.com)

Endocytosis. The active process by which cells transport, in bulk, extracellular and cell surface molecules into the cell via bending of the cell surface membrane to engulf the cargo. The above explanation gets you two marks on an exam. Simple, right?

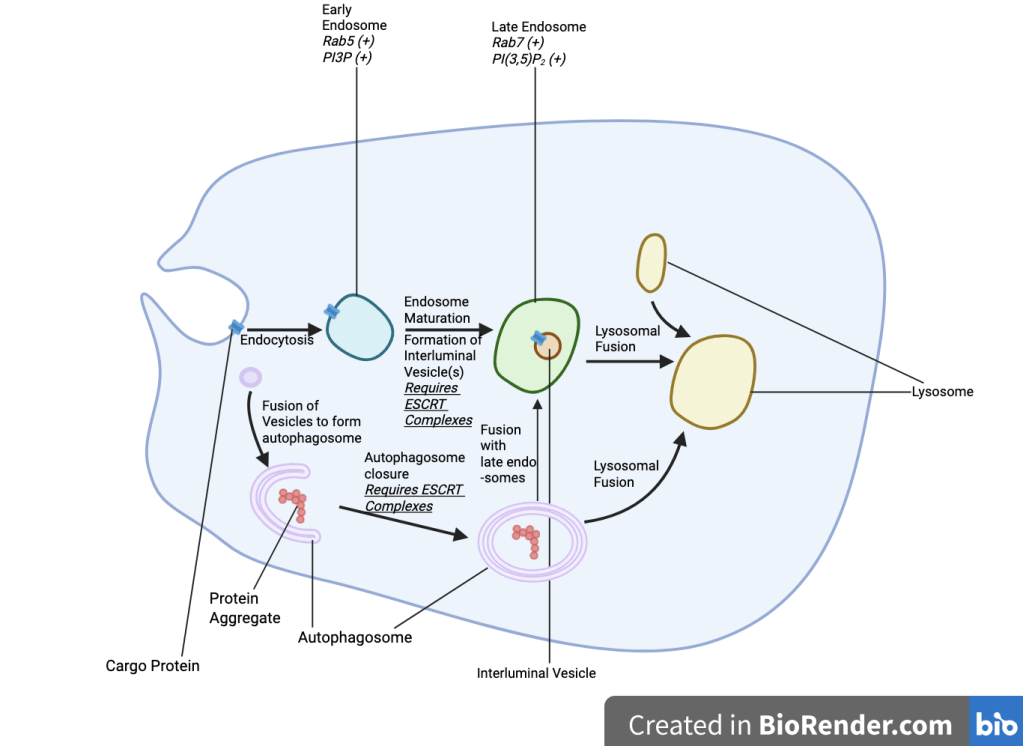

Unfortunately, evolution has left the eukaryotic cell a far more complex organism than I would like as a student. And one such complex process is what happens during endocytosis after the uptake of molecules (see Figure 2). This process involves a membrane-bound compartment known as the endosome, the loss of function of which can lead to a wide range of damaging diseases, ranging from neurological to metabolic.

Figure 2: Further processing and degradation of cargo proteins taken up via endocytosis, along with the role of endosomes in autophagy. (Created using Biorender.com)

The endosome is an intermediate body that sorts cargo proteins taken up via endocytosis, determining if they should be recycled or degraded. As we shall see, the latter in particular is vital for the health of organisms from unicellular yeast to multicellular humans. This endolysosomal degradative function is regulated, largely, by a series of protein complexes known as the Endosomal Sorting Complexes Required for Transport (ESCRT).

The role of the endosome in endocytosis deserves some scrutiny. Upon formation of an endocytotic vesicle via invagination of the cell surface membrane, it brings cell surface proteins to the early endosome where it fuses. Notably, the early endosome is defined by unique membrane surface markers Rab5 and phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphates (PI3P). Then, some cargo proteins are recycled back to the cell surface membrane, and others trafficked to the Golgi body, while those tagged by ubiquitin are degraded. This is accomplished during endosomal maturation, which involves 2 processes, the modification of membrane surface markers and the activity of ESCRT complexes. For the first, Rab 5 is replaced by Rab 7 and PI3P is phosphorylated to form Phosphatidylinositol-3,5-diphospate (PI(3,5)P2). Regarding the second, ESCRT subunits bind to the membrane surface PI3P and the ubiquitinated cargo protein. Sequential recruitment of the rest of the ESCRT then occurs.

Next, the fully assembled ESCRT system facilitates the invagination of the endosome’s membrane to transfer ubiquitin-bound cargo proteins onto the surface of interluminal vesicles within the endosomal lumen, where cargo proteins are exposed to hydrolytic enzymes. These hydrolytic enzymes are delivered by lysosomes fusing the endosome. Once degradation is complete, the remaining endosome is no different from a lysosome. Already, at the cellular level, loss of function mutations induced in ESCRT genes often results in abnormal endocytosis and sorting in eukaryotic cells from yeast to mice.

In addition, to degrade large structures from large protein aggregates to defective organelles, the cell undergoes autophagy, which involves the formation of an autophagosome around the target macromolecule that then fuses with a late endosome or, less frequently, a lysosome. In any case, closure of the autophagosome also requires at least a few ESCRT Complexes. As such, endosome maturation and the ESCRT must be regarded as critical for efficient autophagy.

And this process is what links the endosomes to neurodegenerative disease. One of the root causes of many neurodegenerative diseases, from Alzheimer’s disease (AD) to Huntington’s and Parkinson’s diseases, is the accumulation of protein aggregates within neurons, which eventually kills them . And due to the size of such aggregates, it often falls to autophagy to get rid of such aggregates. Autophagy that requires mature endosomes. Hence, a causal link between loss-of-function mutations of some of the genes encoding ESCRT components and certain forms of dementia has been established. In particular, these mutations have been observed to lead to the accumulation of undegraded autophagosomes – likely due to the lack of mature endosomes to fuse them.

Moreover, the consequences of endosomal dysfunctions are not limited to neurology. Indeed metabolic diseases like diabetes can be exacerbated by endosomal dysfunction. As we were taught in A levels, Type 2 diabetes is defined by insulin resistance and a decreased rate of insulin secretion by beta cells. While the mechanisms by which one’s genotype, lifestyle, diet and age can lead to insulin resistance are complex, a dysfunctional ESCRT system can make matters worse. In particular, the early endosome-associated GTPase Rab5, through one of its effector proteins (APPL1), enables active insulin receptors taken up by the cell to continue signalling for glycogenesis within the early endosome. Unsurprisingly, a correlation between families in which loss-of-function mutations in the APPL1 gene are prevalent and higher rates of diabetes has been established.

Finally, it must be noted that this is a continuously evolving field. In recent years, even more biological roles for the endosomes and ESCRT complexes in particular have been found. From repairing holes in lysosomes to regulating the degradation of damaged nuclear pores, more functions of endosomes and the ESCRT are uncovered each year. As such, I look forward to writing on this subject again.