Writer: Celine Tedja

Editor: Madeleine Hjelt

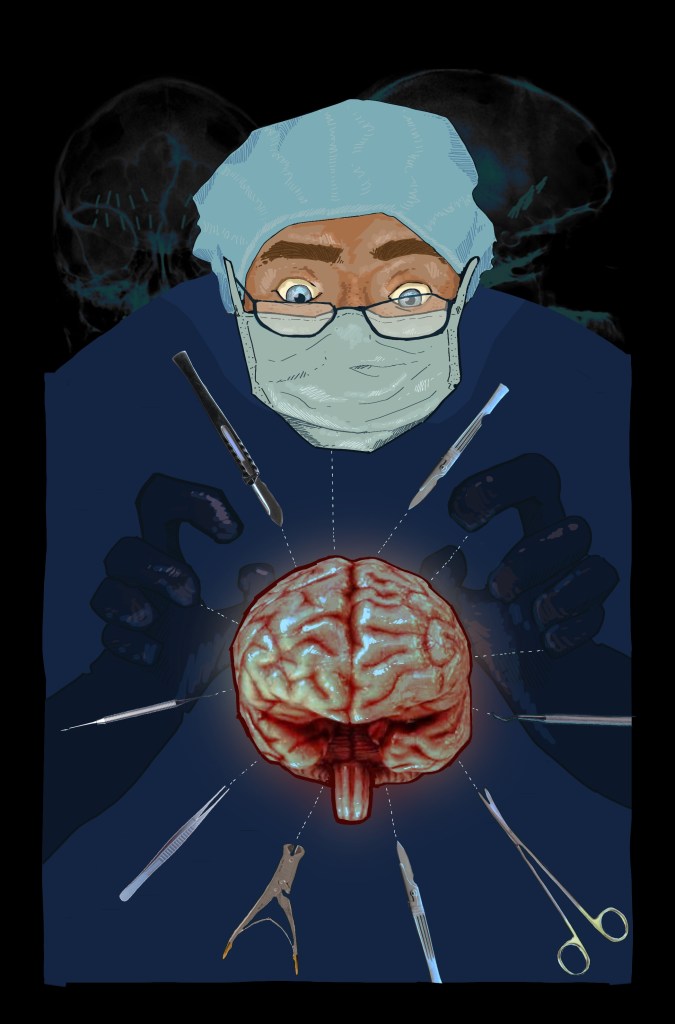

Artist: Ayesha Hyder-Burney

With a growing awareness of the strong connection between mental health and quality of life, the management of mental health issues has undergone significant revolutions over the past decades, driven by innovations in holistic approaches. However, the long history of mental disorder treatment did not come without controversies. One of the most striking examples is psychosurgery, a surgical method for mental disorder treatment that briefly gained widespread popularity during the mid-20th century, mainly in the US. The lobotomy, perhaps the most infamous form of psychosurgery, is likely the one you’ve heard of. Despite being perceived as a viable and powerful option at first, psychosurgery rapidly declined due to ethical issues and unanticipated detrimental consequences for patients. Until today, psychosurgery serves as an interesting case study to reflect on the importance of comprehensive research and ethical standards in medical practice, far beyond focusing solely on short-term results.

Psychosurgery is the surgical destruction of specific nerve pathways in the brain in an attempt to influence behaviour and alleviate psychiatric symptoms. The general idea behind this procedure is that certain parts of the brain are responsible for certain symptoms, and therefore, disrupting the nerve connections in these parts is believed to help alleviate the associated symptoms.

Interestingly, the history of surgical interventions to treat mental health issues may date back as early as 6000 B.C. A practice known as “trepanation” or “trephination” performed during this period involved drilling a permanent hole in the patient’s skull. According to discovered evidence, there might be several motives behind this. The procedure was primarily performed for medical reasons, such as to treat headaches, epilepsy, and mental illnesses, as well as for spiritual purposes. However, more investigations are needed to better understand how this practice emerged and spread across regions.

It was not until the 1930s that the term “psychosurgery” was coined by the Portuguese neurologist António Egas Moniz. During this period, he introduced the prefrontal lobotomy (or leucotomy) to treat mental conditions such as depression and schizophrenia. The procedure involved drilling two small holes in the skull and severing the white matter fibres in the frontal lobe, a part of the brain responsible for personality, reasoning, and decision-making. He suggested that disrupting these fibres would help cure patients’ mental illnesses. In the first few procedures performed, Moniz claimed multiple successful cases, which quickly caught international attention. His technique was later adapted and advocated by the US neurologist Walter Freeman and neurosurgeon James Watts. Their findings in 1942 stated that out of 200 performed lobotomy procedures, 63% of patients improved post-lobotomy, 23% observed no change, and the rest (14%) worsened or died due to complications – statistics that, in hindsight, were misleadingly optimistic.

Freeman introduced the transorbital lobotomy in 1946, also known as the “ice-pick” lobotomy, which he claimed to be more time-saving. This involved hammering a sharp ice pick through the eye socket into the brain’s frontal lobe to sever nerve connections. In 1949 alone, over 5,000 procedures were performed in the US, making this the peak era for psychosurgery. In the same year, Moniz, who first introduced psychosurgery, received a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his pioneering work. Initially reserved for severe psychiatric cases, psychosurgery practice soon expanded to treat a wider range of conditions. Despite some reported irreversible and devastating consequences, such as cognitive and speech impairment, incontinence, seizures, and even death, psychosurgery continued to gain traction, as no other treatments for mental disorders were widely available at that time.

To no surprise, the spotlight on this invasive practice did not last very long. In the 1950s, the increasing awareness of psychosurgery’s dangers sparked a public backlash. Many procedures were even performed without patients’ informed consent. Moreover, the introduction of antipsychotic agents such as chlorpromazine to treat mental disorders further escalated the decline of psychosurgery, as they were evidently more effective and safer for patients. Later on, the development of a greater variety of psychotropic medications, together with the escalating concern and negative perception towards psychosurgery, shifted people’s interest towards medication and away from psychosurgery, marking a new disruptive era in mental health management.

So, is psychosurgery completely neglected now? The answer is no; however, they are only used in extreme cases and hence are very rarely performed. The techniques used also differ from the past controversial psychosurgery. The modern-day surgical intervention is termed “neurosurgery for mental disorder” (NMD), in which surgeons create lesions in targeted parts of the brain using heated probe tips, utilising MRI scans as a guide. In the UK, the main types of NMD include anterior cingulotomy and anterior capsulotomy. These procedures cannot be performed without the patients’ consent, in accordance with Section 57 of the Mental Health Act 1983. Moreover, they are only used as a last resort, after other treatments, such as psychotherapy, medications, and neuromodulation, have failed.

Perhaps one of the most important takeaways from the history of psychosurgery is the significance of ethics and integrity in medical practice. Patients’ safety and welfare should always be prioritised by ensuring informed consent and properly communicating potential risks. This case also highlights the importance of extensive research before implementing a procedure on a large scale, as well as having objective criteria to assess the efficacy of a treatment. During the rise of psychosurgery, assessments of its effectiveness and safety were highly biased, with adverse effects often downplayed or ignored to promote it as a novel treatment for psychiatric disorders. Nowadays, various guidelines on efficacy measurements have been established to ensure the validity and reliability of trial data. Moreover, patients’ rights are now thoroughly protected by laws in medical ethics, with one example being the UK’s Mental Health Act, which describes the rights of people with mental disorders regarding assessment and treatment. After all, the ultimate goal of healthcare is to ensure positive patient outcomes across different dimensions of their lives, and this greatly relies on professionalism, compassion, and strong ethical principles.