Author: Alexia Rasnoveanu

Editor: Haowen Xue

Artist: Yasmin

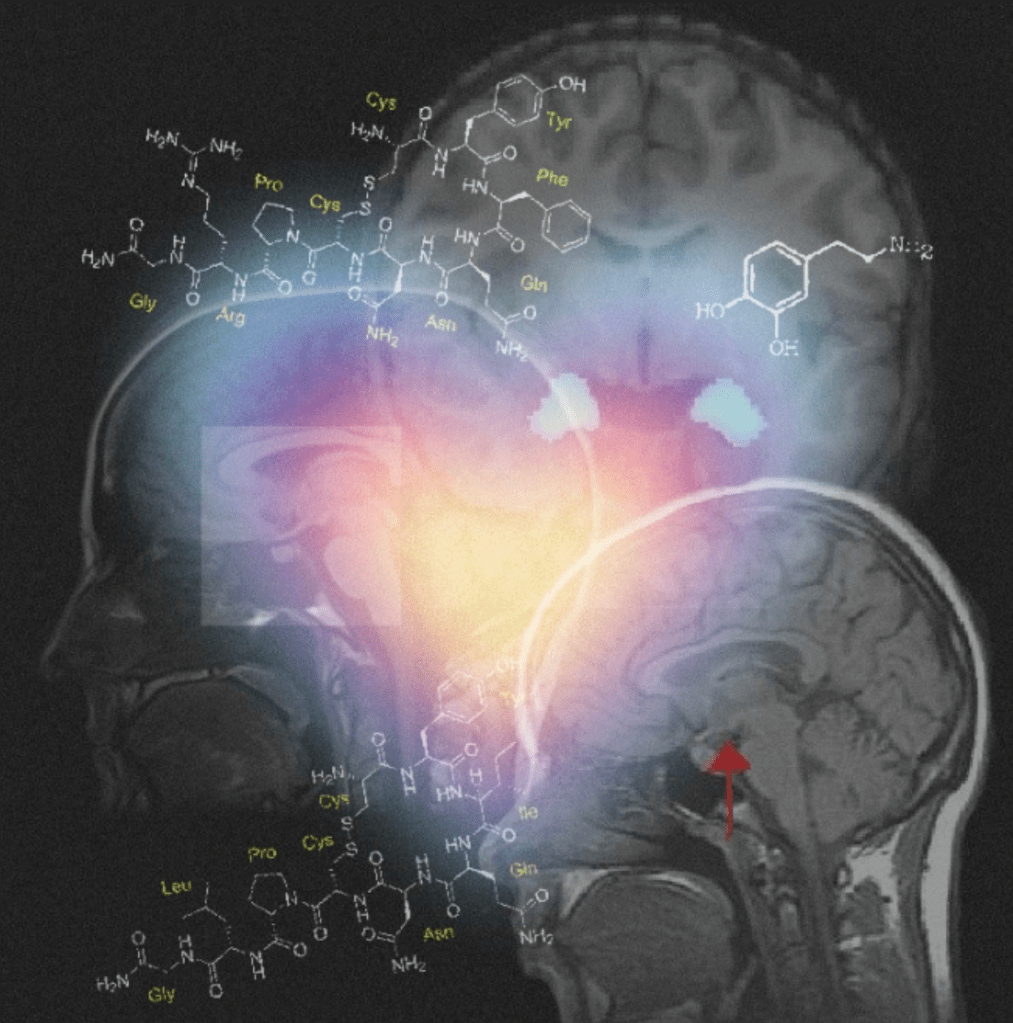

Love is less a mystery than a biochemical symphony. Romantic love? Thank dopamine for the euphoria and the sleepless nights. Platonic love? Oxytocin is at play, cultivating trust and empathy. Familial love? It is hardwired. Love is not just an emotion; it is a survival strategy built into our neural circuitry. Free will or biology? Perhaps love is both, and that is what makes it so captivating.

The science of love is a relatively new discipline with almost 90% of neuroscience literature being published in the last 30 years. Therefore, it is no surprise that the scientific basis of love is often sensationalised, as anthropologists, psychologists, and the general public have attempted to define it for centuries. What we have found is that love is a cocktail of feel-good chemicals that allow us to derive pleasure from this experience. But is love solely a bombardment of neuromodulators and an innate part of our neural composition, or is it something metaphysical?

What happens in our brain when we experience love is dependent on the type of love we feel. We do not hold the same love for a romantic partner as we do for our pet; we do not hold the same love for humanity as we do for our friends and family. Love is multifaceted yet the chemical patterns of it are often overlapping.

Dopamine – produced in the hypothalamus – is widely known as the “love hormone”, and is mainly associated with romantic love. Linked closely to the brain’s reward system, heightened dopamine makes us feel giddy, energetic, and euphoric, even leading to decreased appetite and insomnia, and is triggered by activities we find pleasurable (like the thrill of new love). When someone feels a strong sense of love for a community or even for humanity, oxytocin is typically the most prominent neurotransmitter involved. Oxytocin acts centrally within the brain to control behaviour, especially social behaviours such as altruism and empathy. Oxytocin also triggers the release of serotonin and dopamine when experiencing positive emotions associated with friendship. The combination of these two neurochemicals leads to a more stable mood, creating a long-lasting feeling of happiness and well-being. Innocent love, such as the love for a pet has been shown to lower the stress hormone cortisol, and increase endorphins which instil a sense of comfort and long-term attachment in mammals. Interestingly, in early love, levels of serotonin plunge, explaining the intrusive and overly occurring thoughts associated with infatuation.

Unlike romantic, platonic, or innocent love, love for and from our family is more permanent and unshakeable. It is the one love we cannot quite outgrow, the one bond that is practically programmed to hold on. Unlike friends, who we can exchange like trading cards when our ideals shift, or the fleeting goodwill we might feel toward our communities when convenient, our attachment to family just… persists. So we cannot help but wonder: what makes love for our family so special?

Research from University of Wisconsin shows that neurons found in the central medial preoptic area (cMPOA) are essential for maternal behaviours in mice. In particular, those rich in the calcitonin receptor, which influence behaviours like aggression, anxiety, and sexual drives. From nest building to looking after pups, this receptor plays a unique role in the motivation of motherhood in females, even in situations that evoke fear or disgust. By hyperactivating these neuronal pathways, researchers found that female mice who do not have offspring began taking care of other pups and building a nest with the same care and intensity as if they were their own children. With the flip of a switch, when inhibiting the calcitonin receptor in these neurons, female mice started showing hesitation in retrieving their own pups, even in mildly stressful conditions. So, to what extent is motherhood an expression of free will, and how much is it driven by neurological wiring?

When it comes to paternal love, vasopressin is the key neurochemical secreted in a father’s brain. This neuromodulator is strongly associated with the hypothalamus and the amygdala – areas involved with emotional processing and the fight-or-flight response. Male prairie voles, one of the few mammalian species that exhibit increased paternal involvement, have significantly higher levels of vasopressin. This hormone does not simply make a father “love” his child, it rather imbues them with vigilance, territoriality, and active caregiving behaviours. Similarly, in human fathers, vasopressin strengthens both attachment and protective instincts, becoming an evolutionarily wired imperative to ensure the survival and safety of his child.

On the other side of the equation is the love a child holds for their parents. However, in more scientifically accurate terms, much of what we call familial love is actually described as attachment. In the early stages of life, secure attachment ensures that a child is in proximity to their caregiver and that their brain develops accordingly. This is why custodial care is crucial in early life growth: a child whose parents offer consistent care is neurologically primed for healthy emotional growth. Without parental love in a person’s childhood, the likelihood of adolescent mental health issues is increased; and it all comes down to constant neural stimulation.

Neurons with little neural activity will die, while neurons that are “used” will survive and forge stronger neural connections with each other. As much as certain brain areas can boom with activity, other functions could be lacking from early on if improper care from a child’s caregiver is shown. For example, Romanian orphans reared in physical and social isolation have smaller brains and a larger amygdala than their non-adopted counterparts. The amygdala is a brain area concerned with emotion and fear, thus a larger amygdala would suggest altered emotion and fear processing due to overstimulation and distress. This enormity of brain growth in early life is incomparable to later growth which makes this time crucial.

So what does it mean to love our family? Are we creatures simply a fatality of the primal circuitry of our brains, or are we actually carving out genuine, intentional connections? Even if our loved ones are scripted by proteins and receptors rather than us, what makes the love we hold for our family alluring is its deep roots. We do not love our families despite our biology; we love them because of it, and maybe that is as close to free will as we are ever going to get.