Author: Katharina Stock

Editor: Katie Kavanagh

Artist: Meera Maniar

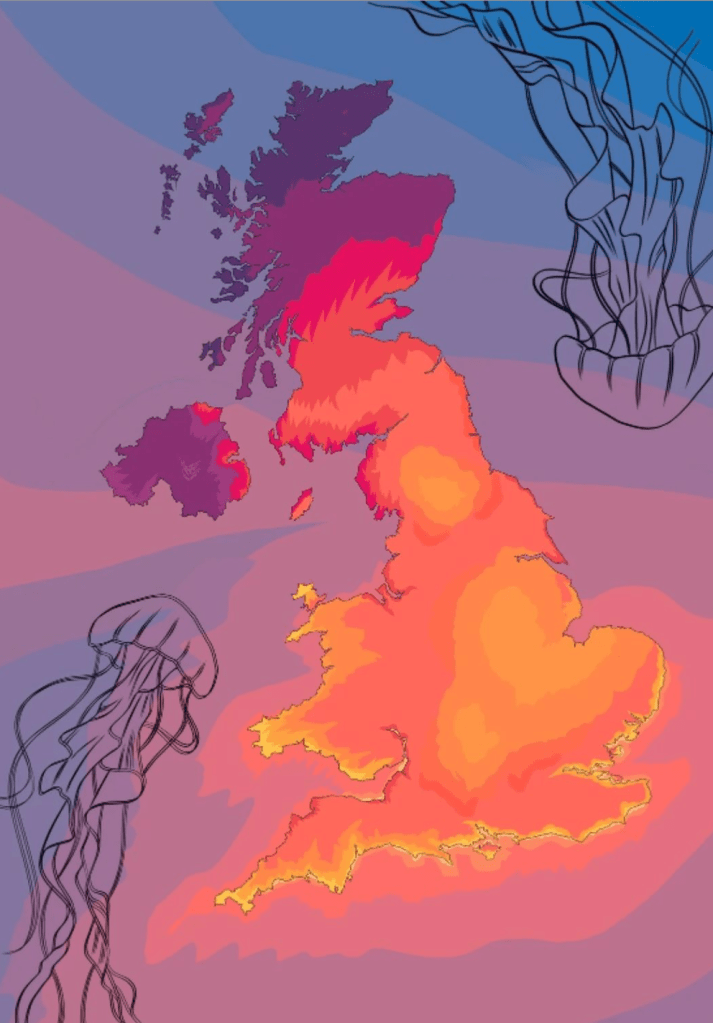

Few thought that marine heatwaves would pose a serious concern in the UK’s cool waters quite so soon. However, in June 2023, scientists sounded alarm bells as sea surface temperatures off the UK and Irish coast rose to unprecedented levels. That month, the Met Office reported temperatures up to 5°C higher than normal.

“Marine heatwaves can cause devastation to marine ecosystems,” says Zoe Jacobs, Senior Research Scientist at the National Oceanography Centre, “They can cause coral bleaching, wipe out seagrass meadows, and severely impact fisheries.”

Marine heatwaves are periods of high ocean temperature that can last days or months. Typically, a period must last five days or more and fall into the 90th percentile in deviation from the seasonal temperature average to qualify as a heatwave. Much like major storms, Jacobs explains, marine heatwaves are natural phenomena, but due to climate change, their frequency and intensity have increased. Since 1982, the number of extreme heat events recorded has doubled.

While the UK does not yet stand out globally in marine heatwave activity compared to more turbulent areas like the North Atlantic, in a recently published study, Jacobs and her team identified regional hot spots. In particular, the southern North Sea, off the UK’s south-eastern coast, seems to exhibit frequent and intense heat events.

Jacobs explains that the region may be more susceptible to marine heatwaves driven by temperature extremes in the atmosphere. Due to the shallowness of the waters in the southern North Sea and the English Channel, heat absorbed by the sea has little room to dissipate allowing the ocean to retain its temperature for longer periods.

Because of the unique geography of the British Isles, this relationship also works in reverse, with marine heatwaves impacting both atmospheric temperature and rainfall in return. Under the right conditions, slow-moving air can accumulate heat and moisture from the sea. The wind then carries this warm and moist air to land, resulting in higher land temperatures and more precipitation. “Because the island is so narrow, you’re never far from the ocean.” Met Office climate scientist Ségolène Berthou explains, “That means that there’s almost always enough wind to bring an anomaly from the sea to land.”

“Our projections show that the temperatures we recorded during the June [2023] marine heatwave will be the average in 2050, so we will likely see more marine heatwaves and ones that are more intense.”

Globally, marine heatwaves have already ravaged ecosystems and caused losses of crucial foundation species such as algae, seagrass, and corals. These species form the basis of the ecosystem with many others relying on them for food and shelter. Losing them, we risk a reduction in fish abundance and an altered species composition, threatening local economies.

However, impacts in temperate regions like the UK are difficult to predict. Kathryn Smith, Marine Ecologist at the Marine Biological Association says, “in the UK we’re only just starting to be impacted by these marine heatwaves.”

Although marine heatwaves typically lead to losses in foundation species, in some cases, they can promote growth instead. Every species has a thermal range in which they can survive comfortably. Smith explains that some species, living in more temperate climate regions, in temperatures on the lower end of what they can tolerate, might benefit from warmer conditions. While this may sound like good news, such events are still likely to impact ecosystem composition more broadly, letting some species thrive as others decline, altering the ecological balance.

Experts were surprised when a paper published in Nature last year reported no impact of marine heatwaves on species like cod and haddock that live near the bottom of the sea in temperate climates. It is possible that fish living in areas like the UK that experience dramatic seasonal temperature differences are more adaptable than others. However, the scale could quickly tip if heatwaves in these regions become more frequent and intense.

For climate scientists, the next step is now to build forecasts which will allow for a more accurate prediction of marine heatwave occurrence. As global sea temperatures continue to rise, extreme heat events are more likely to become precarious. It is important for the UK to prepare for this inevitability and look to other countries, already experiencing more severe conditions, for solutions.

Interviewees:

Zoe Jacobs, National Oceanography Centre, UK

zoecob@noc.ac.uk

https://noc.ac.uk/n/Zoe+Jacobs

Ségolène Berthou, Met Office, UK

segolene.berthou@metoffice.gov.uk

https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/research/people/dr-segolene-berthou

Kathryn (Katie) Smith, Marine Biological Association, UK

katsmi@mba.ac.uk

https://www.mba.ac.uk/staff/dr-katie-smith/