(and more!) What happens when temperature determines sex?

Author: Emma Luo

Editor: Nirvan Marathe

What is temperature-dependent sex determination?

Temperature-dependent sex determination (TSD) is the primary mechanism when determining the sex of reptiles such as sea turtles, crocodiles, and tuataras. Perhaps we are more familiar with genetic sex determination (GSD) in humans and most other animals, where the pairing of sex chromosomes (X or Y) during fertilisation determines sex at conception, with females being XX and males being XY.

However, in species that display TSD, the environmental temperature during egg incubation determines whether the embryo will develop into a male or a female, and variations in incubation temperature lead to the hatching of different sexes. The critical period when temperature has the greatest influence on sex is during the middle third of embryonic development, known as the thermosensitive period (TSP). After this period, the sex of the embryo will be fixed and can no longer be changed by temperature.

Patterns of TSD

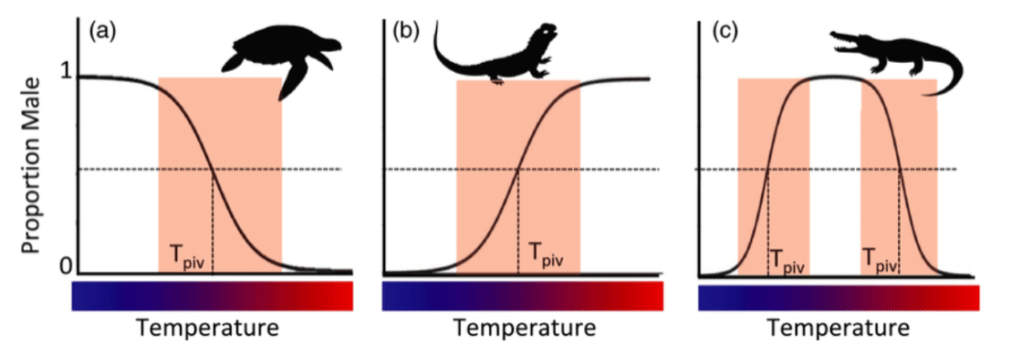

There are two distinct patterns of TSD, where pattern I displays a single transition zone and pattern II displays two transition zones. Pattern I is further divided into pattern Ia. and pattern Ib.

- Pattern IA – Males are produced at cooler temperatures, females at warmer temperatures, e.g., in turtles.

- Pattern IB – Females are produced at cooler temperatures, males at warmer temperatures, e.g., in tuataras.

- Pattern II – Females are produced at cool and warm temperatures, males at intermediate temperatures, e.g., in crocodiles.

Figure 1: The three patterns of temperature-dependent sex determination: (a) type Ia, e.g. sea turtles; (b) type Ib, e.g. tuatara; and (c) type II, eg. crocodiles. The pivotal temperature (Tpiv) is the temperature at which an even proportion of males and females is produced. The red region shows the transitional range of temperatures, where both sexes can be produced,

The Adaptive significance of TSD

Incubation temperature is known to impact reproductive success differently in males and females, where success is defined as the number of offspring an individual can produce over its lifetime. The Charnov-Bull model predicts that selection should favour TSD over chromosome-based systems in cases where parental fitness is enhanced by matching offspring sex to incubation temperatures. In this context, eggs incubated under conditions that promote high male fitness should produce males, while those exposed to female-favorable conditions should develop into females. This results in offspring that are better adapted to their environmental conditions, and leading to greater reproductive success for future generations. This mechanism likely evolved through natural selection due to its adaptive advantage, increasing survival rates and allowing offspring to thrive in specific temperature conditions

Historically, lineages with TSD have survived significant climatic shifts, such as the rapid warming following the Younger Dryas period (12,900 to 11,600 years ago) during the Pleistocene, as well as abrupt temperature increases of up to 5°C over mere decades during the Holocene. Species like sea turtles, which exhibit pattern IA TSD, may have used TSD to their advantage during these warming periods. By shifting sex ratios to favour female offspring in response to higher temperatures (even though such conditions reduced overall offspring viability) ,the population could maintain stability. A higher proportion of females allowed for greater reproductive output (more offspring produced), increasing the chances for genetic variation and the emergence of adaptations to new environmental conditions. This coadaptation of sex ratio and survivability likely contributed to the resilience of species like sea turtles in the face of climate change.

Who has the say in this – if TSD and GSD lie side by side?

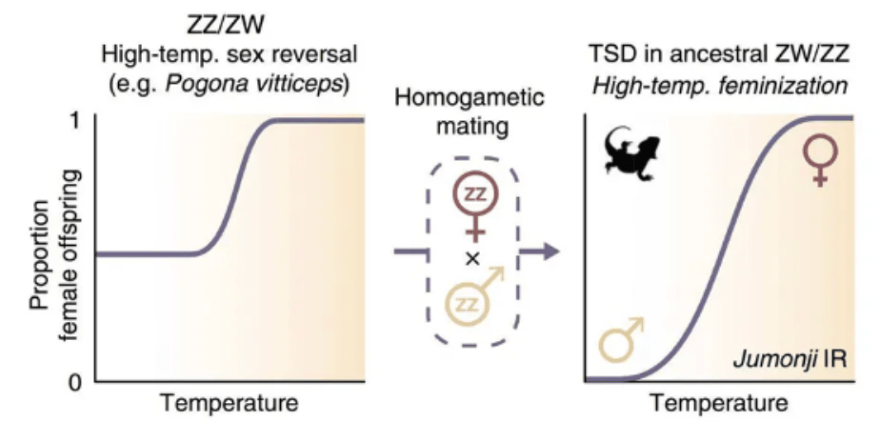

Rising temperatures due to global warming had a significant impact on Australia’s bearded dragon lizards, as high temperatures have overridden their chromosomal sex determination system:

- When eggs are incubated below 32°C, sex is determined by the sex chromosomes of the parents (Z or W), with females being ZW and males being ZZ

- When incubation temperature rises above 32°C, an increasing number of eggs develop into females, regardless chromosome combination

- When temperature exceeds 36°C, all genetically male (ZZm) dragons develop into females (ZZf) in appearance and can lay eggs

Moreover, these temperature-induced female dragons (genetically ZZ males) produced more eggs than typical ZW females. Their offspring no longer display genetic sex determination (GSD), as the pairing of ZZf and ZZm will consistently produce ZZ offspring, whose sex is entirely temperature-dependent. With global warming, the frequency of temperature-driven sex reversal is expected to rise. If this trend continues, scientists predict a possible future loss of the W chromosome entirely.

Figure 2: Model showing mating of sex-reversed and wild-type homogametic individuals causes transition to TSD. Left: Ancestral GSD states (ZZ/ZW), with sex reversal to female at high temperatures. Right: TSD patterns emerge, with female-specific at high temperatures and male-specific at low temperatures, and the loss of the W chromosome.

What’s happening to them right now?

Contemporary climate change imperils species that rely on temperature-dependent sex determination. Since the industrial revolution, human activity has driven a dramatic increase in greenhouse gas emissions, resulting in a rise of approximately 0.2-degree Celsius in global mean surface air temperature per decade. This unprecedented rate of warming coupled with the lack of historical events to guide future predictions, places TSD species at significant risk of developing skewed sex ratio, which could ultimately lead to demographic collapse. The impacts of climate change are already evident in behavioural shifts observed among TSD species. For instance, many species with patterns IA and II have started to nest earlier in the year as an attempt to preserve sex ratio. However, the rate of these adaptive changes is unlikely to match the rapid progression of global warming. As a result, many TSD species face a heightened risk of extinction or may be forced to evolve mechanisms such as genetic sex determination to survive. To save TSD species from extinction and ease global warming, we require a combination of immediate actions, such as habitat protection and artificial nesting efforts, and long-term solutions like transitioning to renewable energy and reducing carbon emissions. Everyone has a role to play, from individuals adopting sustainable lifestyles to governments enacting robust climate policies. By acting now, we can give these unique species a fighting chance to thrive in a changing world.