Author: Callista Chan

Editor: Altay Shaw

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder affecting the brain and the central nervous system (CNS). Marked by a progressive decline in cognitive function, AD—amongst other conditions—is a leading cause for dementia, prompting memory loss, disorientation, and other trademark symptoms of AD. Nonetheless, recent findings by Danish neuroscientist Maiken Nedergaard have led to major strides in our understanding of AD, marking a vital shift in current paradigms of neurophysiology. Indeed, it seems the recent discovery of the glymphatic system may be the key to developing pioneering therapeutics for neurodegenerative prion disease.

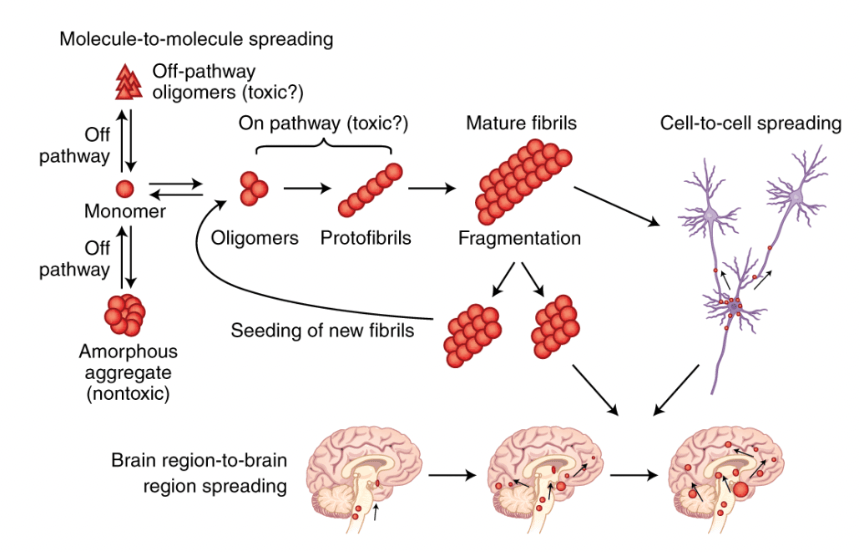

The pathology of AD has been well established for decades. While AD has a genetic link, it is the current thought that AD – as well as Parkinson’s and other neurodegenerative disease – is attributed predominantly to protein misfolding in the CNS. Much research has linked AD to the deposition of proteins amyloid-beta and tau in key regions of the brain, most notably the hippocampus, which plays a vital role in memory consolidation. Indeed, it is the aggregation of structurally abnormal proteins that is directly responsible for dementia and other hallmark symptoms of AD, giving the disease its rightful classification as a proteinopathy.

Figure 1. Protein misfolding – followed by the deposition and aggregation of structurally abnormal proteins – is thought to be a leading cause of AD and other neurodegenerative disease. Misfolded proteins act as a template – in scientific terms, a prion – enabling normally folded proteins to adopt an irregular structure. This prion-like behavior facilitates the assembly of large stable aggregates such as amyloid plaques and tau tangles. Additionally, intercellular transmission expedites the proliferation of aggregates to separate regions of the brain.

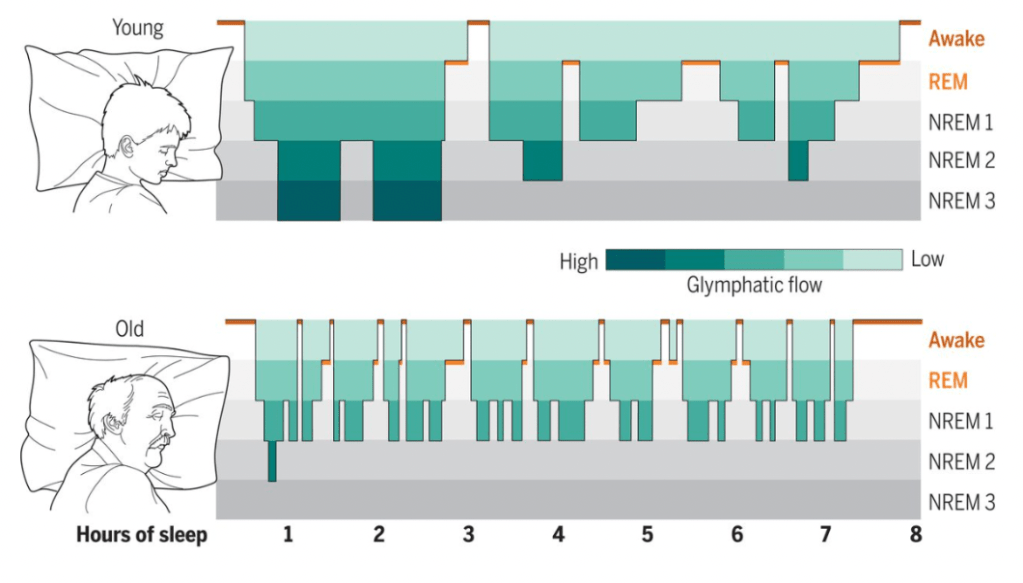

This revelation raises a key question. What factors predispose proteinopathies? Indeed, observing groups afflicted with AD, it appears the disease is common in old age – often, affecting individuals aged 65 and above. However, the answer to this question extends beyond age alone. Age significantly reduces the quality of sleep; the elderly rarely reach Stage 3 NREM sleep, and most frequently experience disruptions in Stage 1 and 2 NREM sleep. Indeed, it seems to be the debilitated sleep – accompanied by old age – that is predisposing elderly people to AD and other neurodegenerative proteinopathies.

Figure 2. The glymphatic system is thought to provide a mechanism of waste – i.e. protein – removal in the CNS. It is made of glial cells – astrocytes – as well as perivascular spaces situated between neural blood vessels and astrocytic endfeet. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) enters glymphatic regions via perivascular spaces; a process facilitated by aquaporin-4 (APQ-4) channels in the astrocytic endfeet. After, CSF mixes with interstitial fluid (ISF), eliminating metabolic waste products. The CSF exits glymphatic regions via perivenous pathways, returning to the subarachnoid space; glymphatic clearance is completed when ISF is drained by the meningeal lymphatic system.

The validity of this hypothesis is corroborated by recent studies on glymphatic function. Much research has indicated that glymphatic activity is largely dependent on sleep. In vivo 2-photon imaging of glymphatic function revealed a 90 percent reduction in CSF influx in wakeful mice when compared to rodents in both a natural and anaesthetised sleep state. Indeed, it appears glymphatic function is conserved in a wakeful state, ultimately preventing the clearance of metabolic wastes.

Figure 3. The visual above illustrates a hypnogram constructed from EEG recordings of sleeping mice. The green shading denotes the proposed efficacy of glymphatic function. Sleep in young age is continuous; characterized by slow-wave brain activity as well as deep NREM cycles. Meanwhile, sleep in elderly is often disruptive; marked by a domination of superficial Stage 1 and 2 sleep. Indeed, it is the weak turbulent nature of sleep that serves to disrupt glymphatic function in old age; ultimately, predisposing elderly to AD and other proteinopathies.

What does this mean for patients afflicted by late-onset AD? The discovery of the glymphatic system – albeit a groundbreaking paradigm – is still nonetheless a recent revelation. While our understanding of glymphatic activity has evolved over the past decade, exploiting its function as a means of pioneering therapeutics is a branch of pharmacology that has not been explored sufficiently in-depth. Despite this, the last decade has seen several brave attempts at confronting this task. A promising rodent study – published quite recently – revealed a heightened glymphatic flow in wakeful mice upon exposure to non-invasive gamma stimulation at 40 Hz. With various follow-up studies being conducted on the matter; this potentially establishes gamma stimulation as a novel strategy in tackling AD – as well as other neurodegenerative proteinopathies – in future therapeutic ventures.