A brief exploration of chimerism in humans and what it entails.

Author: Savina Hui

Editor: Altay Shaw

What image does the term “chimera” conjure up for you? A ghastly beast with the body of a fire-breathing lion, a goat protruding from its back, and a serpent in lieu of a tail? While the Greek monster Chimera is certainly the origin of the word, chimera in biological terms has an immensely different definition.

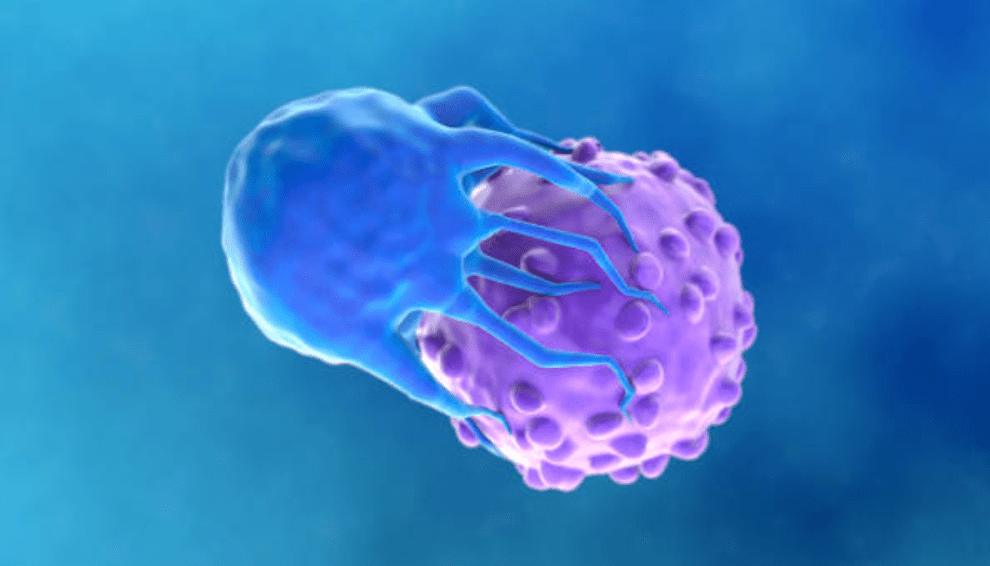

Chimerism occurs when there are two or more genetically distinct cell lines in the same organism. While rare, it is a condition that can arise naturally in all multicellular organisms, including humans.

Generally, there are considered three types of natural chimerism: microchimerism, fusion chimerism, and twin chimerism. Microchimerism occurs when foetal-maternal cells travel across the placental barrier, causing foetal cells to be found in maternal blood and maternal cells to be found in the foetus’ bloodstream. The presence of foetal cells in maternal blood, or maternal cells in the child’s blood, can persist for decades, causing microchimerism. Fusion chimerism takes place when two diploid cell lines fuse. The most typical occurrence of fusion chimerism is tetragametic chimerism, in which two diploid zygotes fuse together to form a single 4n zygote. Lastly, twin chimerism arises when one embryo in a set of dizygotic twins dies. The surviving embryo absorbs cells from its deceased twin, giving the living embryo two sets of DNA.

Artificial chimerism can also occur in humans after organ transplants. The donor’s genome is introduced alongside the donated organ, which may sometimes result in graft chimerism. In 1969, a study first demonstrated this, revealing that the recipient’s cells replaced the Kupffer cells, even though the majority of the transplanted liver’s tissue still contained the donor’s genome. In the case of a bone marrow transplant, the production of red blood cells by the donated bone marrow may cause the recipient’s blood type to shift to that of the donor’s or become a mix between the donor and the recipient. The donor’s genome may completely replace the recipient’s bone marrow’s DNA as the donor’s bone marrow regenerates.

With the dramatic imagery the Greek Chimera calls upon, one cannot be faulted for believing chimerism to be an obvious and visible condition. However, although chimerism can occasionally lead to intersex individuals, DNA testing is necessary to detect most chimerism. Even in cases where chimerism is expressed in the phenotype, the physical characteristics shown are often inconspicuous—such as heterochromia or differently coloured patches of skin.

Chimerism in most individuals remains undetected, which may lead to issues during DNA testing. False negatives can occur in parental tests, with one case showing an uncle-nephew relationship between the father and son. This is often due to the parent exhibiting twin chimerism, which may lead to the child inheriting alleles from the deceased twin embryo the parent absorbed in the womb rather than the parent’s own DNA. As DNA profiling is sometimes employed to investigate a crime scene, chimerism can also lead to difficulties in forensic science. Natural chimerism may reveal a mixed genetic profile, while artificial chimerism—particularly when it is induced by bone marrow transplantation—may cause blood samples to present both donor and recipient DNA, or even solely donor DNA. To ensure proper justice, we must account for this.

To conclude, chimerism is a condition in which at least two genetically distinct cell lines exist in the same organism. Both natural and artificial chimerism can occur in humans, but it usually remains undiscovered for a person’s entire lifetime. Chimerism often only shows up during DNA testing, which may cause issues such as false negatives in parental tests.