Author: Marta Sadlej

Editor: Altay Shaw

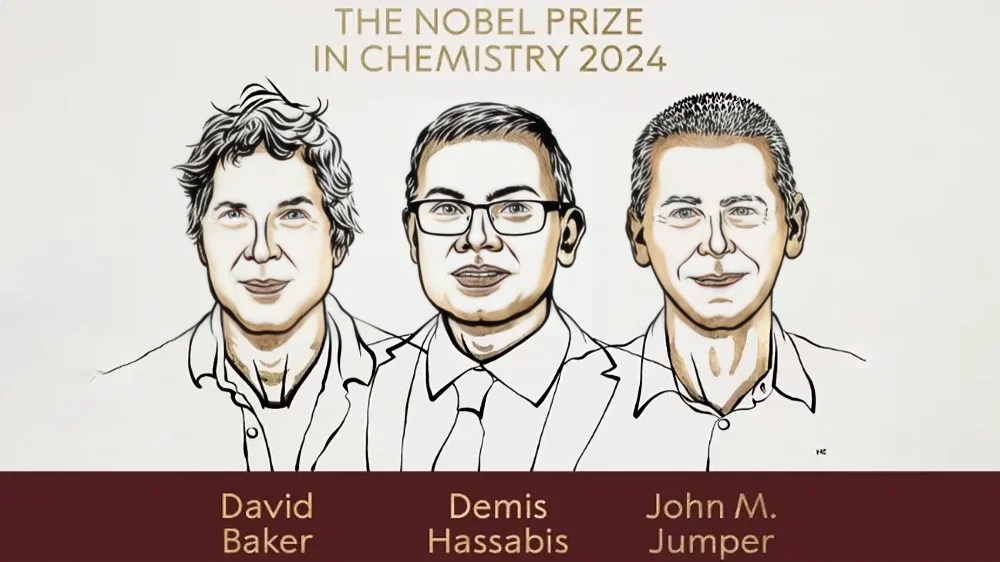

Demis Hassabis (a UCL alum!), John Jumper, and David Baker received the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their groundbreaking contributions to protein structure prediction and design, in an exciting announcement that shook the scientific community. This award not only recognises the monumental advancements in computational biology but also highlights the significance of understanding protein structures—a feat that has implications across various scientific fields, from drug discovery to synthetic biology.

As I sat in a lab meeting when the news broke, I felt a surge of excitement; the recognition for protein structure prediction reflects the transformative developments that have taken place in just a few short years. While research into protein structures has been ongoing for more than 50 years, it is only recently that the field has reached a tipping point. A huge number of possible interactions between residues and secondary structures forms a sophisticated problem of determining the three-dimensional structure of proteins. Through a tremendous effort by crystallographers, over 225,000 protein structures have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) over the decades. However, with the advent of machine learning and artificial intelligence models, along with advancements in computing power and the availability of massive datasets, researchers can now gain an understanding of newly sequenced proteins without resorting to exhaustive lab investigations. This shift allows scientists to focus limited resources on the most promising targets.

The Importance of Protein Structure

At the heart of this recognition is the essential role that protein structure plays in understanding biological processes. The central dogma of molecular biology states that DNA transcription results in RNA, which subsequently translates into proteins. However, the sequence of amino acids alone—known as the primary structure—does not determine a protein’s function. The intricate folding of these chains into specific three-dimensional shapes, or secondary and tertiary structures, is crucial for their activity. Understanding these structures allows scientists to decipher how proteins interact, how mutations affect function, and how they can be targeted for drug development.

Traditionally, experimental methods such as X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) have been employed to determine protein structures. However, these techniques can be time-consuming and costly, often taking years to yield results for a single protein. This is where computational methods have revolutionised the landscape.

The Breakthroughs

John Jumper, Demis Hassabis, and their team at Google DeepMind introduced AlphaFold2 in 2020 at the Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) competition, where it achieved unprecedented accuracy, especially on difficult targets. This machine learning-based approach utilises deep neural networks to analyse the relationship between amino acid sequences and their corresponding structures. It learns from the vast repository of experimentally determined protein structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) to predict how a given sequence will fold. A key aspect of AlphaFold’s success lies in its use of co-evolution data—by analysing multiple sequence alignments, it identifies evolutionary correlations that suggest how residues interact within the folded protein structure.

At the Computational Structural Biology conference in December 2023, John Jumper discussed the intricacies of the model. The small improvements, alongside the careful selection of functional loss and uncertainty prediction were quintessential to creating a functional model that AlphaFold2 has now become. It is remarkable to think Jumper has achieved so much in short space of time, given he only graduated PhD back in 2017 and now, becomes on the youngest recipients of the Nobel Prize.

Another challenge was designing proteins never-before seen in nature. David Baker’s contributions with the Rosetta software suite, including the recent Protein MPNN and RFdiffusion models, further pushed the boundaries of protein design. This model allows scientists to determine what amino acid sequences will create desired protein structures, paving the way for the design of novel proteins with specific functions. Since their first successfully protein structure in 2003, Baker’s lab has been instrumental in demonstrating that computational design can yield new enzymes and antibiotics, showcasing the practical applications of this research.

Implications for the Future

As of October 9th, 2024, the AlphaFold2 paper has been cited an astonishing 27320 times, showcasing the vast implications of their discovery (3). For instance, understanding the precise structure of proteins can lead to more effective drug design by identifying how small molecules can interact with specific proteins. This could accelerate the development of therapies for diseases caused by protein misfolding or malfunction, such as Alzheimer’s and certain cancers. Moreover, the ability to predict protein interactions can significantly enhance our understanding of cellular processes and signalling pathways.

The new era of protein structure prediction also holds promise for synthetic biology. By designing proteins that can perform specific tasks—such as breaking down pollutants or producing biofuels—scientists can address critical challenges facing our planet. The integration of computational predictions with experimental validation allows for a more efficient approach to discovering and optimizing these new biotechnologies.

Conclusion

The awarding of the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry to Hassabis, Jumper, and Baker marks a significant milestone in the field of protein structure prediction and design. It not only honours their individual contributions but also shines a light on the collaborative spirit of scientific discovery. And as David Baker highlighted following the announcement, none of the discoveries would have been possible without the foundational breakthroughs that preceded them: “I stood on the shoulders of giants.” – he said. As researchers continue to unravel the complexities of protein structures, we stand on the brink of transformative breakthroughs that could revolutionise medicine, environmental science, and beyond.

In an age where computational biology is reshaping our understanding of life at a molecular level, this award serves as a reminder of the potential that lies in the intersection of artificial intelligence and biology. As we celebrate this achievement, we must also look ahead to the new horizons that await us in the fascinating world of proteins.

NB: If you want to read more, have a look at this Nature article about the prize.