Author: Rachel Cooper

Editor: Emily Vialls

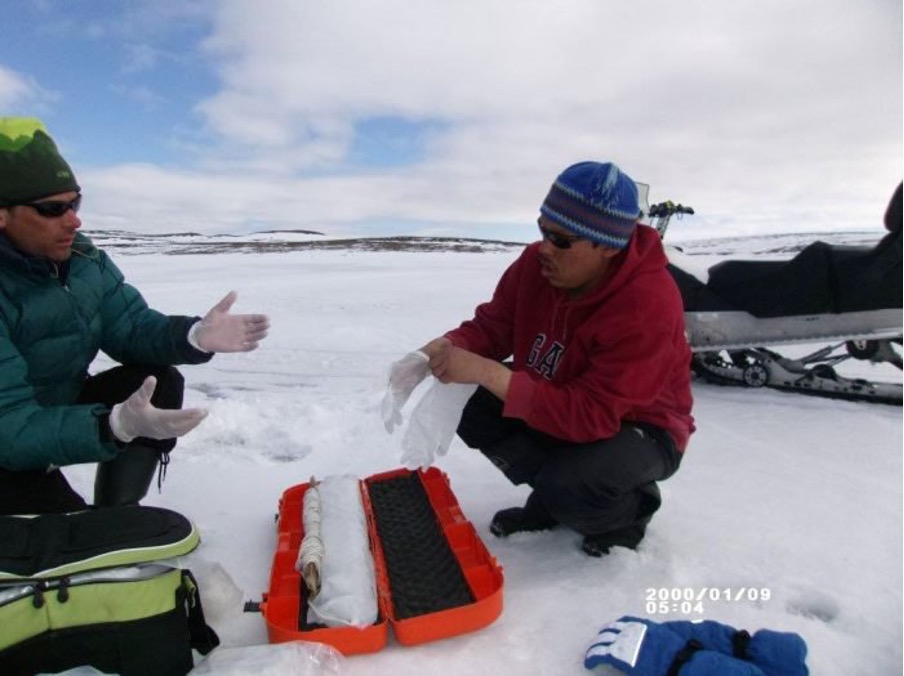

Photo Courtesy: Joeffrey Okalik and Murray Richardson deploy temperatures sensors to thermal stratification in an Iqaluit area lake (Iqaluit, 2014). Photo Credit: Jamal Shirley

Science is often dominated by Western cultures. We have the most funding and resources, and research follows a carefully tailored and structured process. However, it doesn’t represent the different perspectives on nature from cultures all over the world. Limiting our perspective of science may hinder our progress, since we don’t understand the traditional belief systems of indigenous populations. This article focuses on one indigenous culture in particular, the Inuit, who inhabit the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Arctic Canada, Alaska and Far East Russia. They have a rich history of traditional environmental knowledge, which has been passed down through generations. Their unique knowledge of the natural world sources an integral part of their cultural identity, and we could use this knowledge for scientific advancements. It may be the key to protecting biodiversity and achieving sustainable development.

Scientists have used their knowledge in the past to help with their research, and its importance is slowly being recognised. In one example, environmental researcher Shari Gearheard worked with Inuit hunters and elders to examine changes in weather patterns. They agreed the difference between their research methods “brings a completely different emphasis both in defining what the important scientific questions are, and discerning how to address them”. Members of the Inuit community were able to predict the weather with a unique set of skills, but their ability is becoming weaker as the climate changes. By sharing stories of these changing patterns with researchers, they had enough information to analyse their reports. They found a significant decline in temperature persistence in May and June, which aligned with Inuit stories of unpredictable weather variations during this time.

Inuit’s traditional ecological knowledge of animal behaviour along with other natural processes, such as ice conditions, is also invaluable for scientists. Their knowledge of bowhead whale behaviour, dating back thousands of years, was shared with Western scientists, who were able to enhance this knowledge with modern technology. Cross-cultural efforts in this study allowed a special understanding of whale behaviour and population changes, and researchers were able to develop sustainable whaling practices that were respectful of the Inuit culture while conserving a threatened species. Furthermore, knowing the seasonal resting places of walruses is common practice within the culture. In recent years, the Inuit have experienced changing environmental conditions and less predictable walrus migration patterns. This observation was shared with Canadian researchers to develop their study of the migration behaviour and distribution of the species.

Despite the benefits, there is a danger that using Inuit knowledge to our advantage will lead to power dynamics between science practices. Arctic research is often rooted in colonialism, with an academic mindset that privileges the interests of Western institutions and fails to address Northern societal needs. Therefore, while it is good to learn from Inuit cultures for our scientific research, we also need to see more Inuit research coming from themselves. There seems to be a credibility gap between Western and Inuit knowledge, since many people believe their ‘science’ is just myths and stories while the former comes from evidence that is collected and analysed. Inuit traditional knowledge is known as ‘Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit’ (IQ), which encompasses all aspects of traditional Inuit culture, including values, world view, language, social organisation, knowledge, life skills, perceptions and expectations. This highlights the difference between IQ and Western understanding of traditional knowledge, as IQ represents a different way of knowing from centuries of practice. Inuit hunters in particular must be Arctic scientists, wildlife experts, and water and ice researchers to survive; they need this traditional ecological knowledge to examine variations in climate and prey behaviour to catch their food. Therefore, this knowledge is arguably just as important as modern science from Western cultures.

As the use of indigenous knowledge is becoming more recognised and used in research, people are seeing the benefits of explaining complex systems with traditional approaches. However, we should encourage Inuit scientists to contribute their own work to address the issue of Western supremacy. A wide range of research from both indigenous and Western cultures, as well as cross-cultural studies, will provide an immense collection of knowledge and perspectives that will better equip us for the fight against the world’s biggest environmental problems.